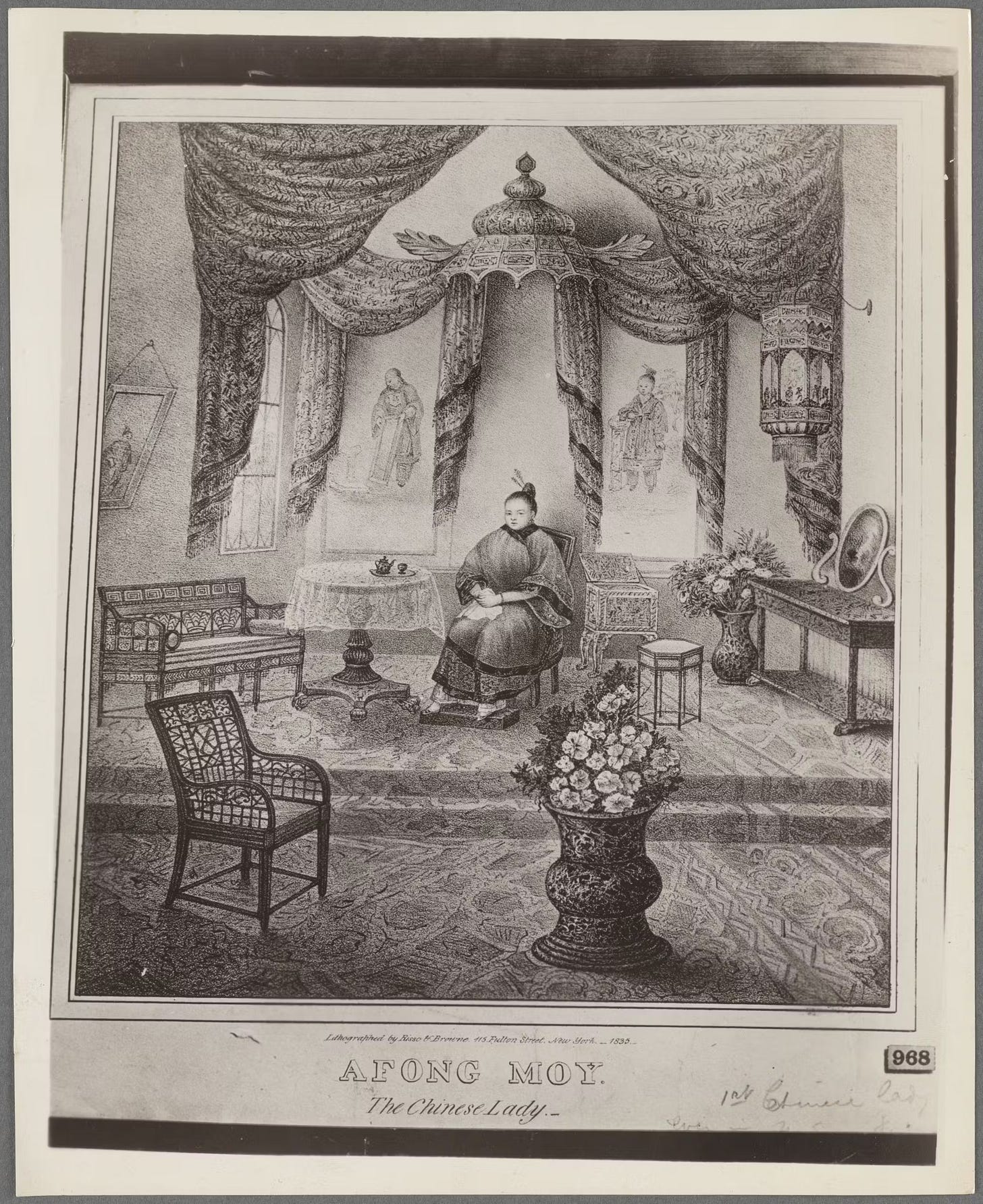

The Chinese Lady

What we can learn about operationalizing narrative strategy from my radio silence of the last month...

Hi, it’s me! At the beginning of the summer, I said that I was going to slow down my Substack publishing cadence from weekly to biweekly, so that I could dedicate some time to my novel. Well, it’s now been four weeks since my last post about socializing counter-narratives and I still haven’t written the final piece in my series on narrative change…it will come! Just not today.

Today, I’m sharing the first chapter of my novel, The Chinese Lady. I started writing it again this summer after a two year hiatus due to other life demands (i.e. having a kid, starting a business). I thought it would be pretty easy to pick it back up. It’s not like I stopped writing—I was writing a Substack about organizational narrative every week! But I quickly realized that my muscles for this particular storytelling endeavor had completely atrophied. The good news: after two months of disciplined routine, I’ve built my novel-writing muscles back up again.

Organizations often agonize about the concept of storytelling cadence. They feel pressure to constantly generate social media posts, blogs, and newsletters. They worry that a lull in storytelling will mean that they’ll lose momentum, be forgotten. But when it comes time to generate content, they might freeze up. They get writer’s block. “What do we say that’s new or fresh this time?” they fret. “How do we even start?”

In a previous post, I wrote that organizations have to root their narrative strategy in clearly defined purpose and impact—what they want audiences to think, know, or feel after engaging with their storytelling. But my novel-writing venture has also newly reminded me of the importance of operationalizing our narrative strategy, e.g. putting in place the routines and processes that help us build and sustain our organizational storytelling muscles.

For example, my daily novel-writing routine has been this:

6:30 AM- 7:00 AM: Clear my inbox, because otherwise my mind will be distracted by what’s going on in there

7:00 AM-7:15 AM: Decide on my writing goal for the day.

7:15 AM- 9:15 AM: Put my phone in another room and write.

When I started this routine at the beginning of the summer, I often sat in a blank stupor at my desk from 7:15-9:15 AM and would maybe type one paragraph. But after 67 days of practicing this routine, I now sit down and take off writing. So, for anybody who enjoys historical fiction, here’s a peek at what I’ve been working on.

The Chinese Lady

“The ship Washington, Capt. Obear, has brought out a beautiful Chinese Lady, called Juila Foochee Ching-chang King, daughter of Hong Wang-Tzang Tzee King. As she will see all who are disposed to pay twenty five cents, she will no doubt have many admirers.”

New-York Daily Advertiser, 20 October 1834

We crossed the ocean in twenty-six weeks.

The ship was rank, the food was more so, and my traveling companions most of all. There was no point in missing home. The captain’s wife taught me English when she could stomach sitting up, which was not often. She told me to call her Miss Margaret. She pointed at me to indicate I should tell her my name. I knew not what to say. Not Third Sister since the captain’s wife was no relation, and Little Sparrow was a mother’s whim. The captain said she should give me an English name. Julia, she called me first, then Daisy. Then she got to reading her Bible and named me Patience, Prudence, Grace. Then it was Amy, then Kitty, and then Daisy again. Twenty-six weeks in total we tossed like pungent nuts in the ship’s briney belly, and I was given twenty-six names. Then one afternoon the Captain cried, “Land ho!” and Miss Margaret crawled from her bunk, still green but weeping with relief, and said, “Julia, now you shall see New York!” and that was the name that stuck, at least for the next five years.

The year Margaret went to Canton, William allowed it only because of Julia. He and the Carnes brothers had decided upon bringing a Chinese Lady back this time, to take center stage in the a grand Exhibition of Oriental luxury goods. Apparently, the sight of an authentic Chinese Lady taking tea in the midst of their exotic porcelain, lacquer and silks would drive the ladies of New York into a frenzy of covetousness for the Carnes’ wares. But there was the matter of keeping everything respectable.

“I suggested to the Carnes that you come along as chaperone,” William said over breakfast, after he had cut and read his newspaper. “I said to them: when we get back, the girl can stay with my Margaret instead of at a boarding house. Everything will be right and proper, with my Meg involved, I said.”

“A Chinese Lady!” Margaret said. “What am I supposed to do with her?”

“She’ll be company for you,” William said.

“I don’t know how she can be,” Margaret said. “I don’t speak Chinese.”

“She may speak a little pidgin. And you can teach her English. Isn’t that what you did before I saved you? Poor little Miss Haskell! The overworked governess,” William teased.

“I was a schoolteacher,” Margaret said.

“And very unhappy you were, too,” William said, because he insisted on believing that any woman making her own way in the world was to be pitied. It would be useless to try to convince him otherwise. He would indulge her and call her a brave, silly puss. Then, indulging her always seemed to bring out the amorousness in her husband, and it was awful to have to go back to bed and feign shy rapture at eight o’clock in the morning. Anyway, Margaret couldn’t remember whether she’d been happy or not as a schoolteacher. She only remembered feeling relieved that her modest salary meant that she could rent a cottage and didn’t have to go live off the charity of some distant relative. Thank goodness the previous schoolmaster had married and gone off to Boston in the middle of the school term and that the school board—torn between their doubts that a woman could do the job and obligation toward the daughter of one of the school’s greatest patrons—had deigned to give her the post.

She’d presided over the little rented cottage and the schoolhouse in Salem for two whole years before she had met William. It had been at the Siddons’ Christmas party. The high-nosed Siddons usually wouldn’t have deigned to invite a spinster schoolmarm, but Miss Haskell’s father had given Mr. Siddons his start. So the invitation had arrived at the rented cottage, Margaret had gone to the party, and there young Captain William Obear had been in a splendid new coat. He’d been one of the prizes on the marriage mart: just thirty, with all his own teeth and legs not bandied despite years at sea, and carrying great prospects, for he, unusually, owned the ship he sailed. It had seemed wondrous that he should single out Margaret in her plain poplin dress—gray half-mourning for her father (twenty-six months dead but why waste good material)—from the flock of gaily dressed debutantes. But he had crossed the room almost immediately to bend over her hand. Over the waltz, that slightly scandalous dance during which a gentleman could hold a lady close, William had intoxicated her with stories of his journeys to the Far East: the Flower Boats in Canton Harbor, the exotic smells of the wharf, the tiny gentlewomen with their tiny, miraculous feet whom no white man ever laid eyes on because they were closed up in their great courtyards, as walled-up as maidens in the castle tower.

She had believed, once, that he would take her with him on such grand adventures. When he’d proposed, he’d said: “There’s no better wife for a captain than another captain’s daughter. You’re a quiet little thing, Miss Haskell, but you’ve got mettle!” Joy bloomed. She’d seen the gates opening. William wanted a wife with mettle! Surely, he meant that that his wife would need to brave the trevails of long weeks at sea, the impudent consideration of slanted foreign eyes, the conversation of the rough men who worked in his employ. Margaret would surprise and delight him with her knowledge of the compass, of the stars mapping out the night sky. The prospect had left her breathless. She had been moved to tears. The tears had undid William’s self-restraint. He had taken her then and there upon the threadbare chaise lounge in the front parlor of the rented cottage. Well. There had been no question of not marrying him after that.

A month after their nuptials, William sailed off alone. By mettle, Margaret realized, her new husband had meant the fortitude to say farewell, over and over, to wait alone at hearth and home for ten months at time, and to welcome him back each time without reproach. She had no opportunity to mention her skill with the compass or her knowledge of astronomy. The morning of his departure, William presented her with a box of silk threads and ribbons. “Trim yourself a hat, my girl,” he said, chucking her under the chin. “The anticipation of seeing you in it will warm my dreams at sea until I’m back.” William didn’t mind if she begged him to take her along, wept at his going, or asked upon his return if he might be longer at home this time. He liked it. He took her desperate pleas for ploys to remain at his side, her tears of fury for those of heartache, her trepidation at the answer for timorousness at asking a question. He swelled with pity and fondness, a combination that always converted into amorousness, and in the enthusiastic gymnastics over her body that inevitably followed, he panted things like, “Poor little Meg! My poor darling girl!”

Margaret resigned herself to her fate. No use in sentiment that he would only misinterpret. The best course of action was to keep him hale, so that she might not become an impoverished widow so shortly after having been an impoverished orphan. Upon his going, she packed his pockets with limes to ward off the scurvy and put her mother’s cross about his neck. Upon his arrival, she inquired as to the length of his stay in the punctilious tones of a housewife taking stock of her housekeeping budget—no more—so that she might increase her order accordingly with the green grocer and butcher.

And now, after seven years of marriage, William was asking her to come with him to China! She thanked God. She blessed dear William. She blessed the impetuous Carnes brothers, for surely they had come up with this harebrained idea. It didn’t matter whether this girl the Carnes wanted spoke Chinese. It didn’t matter whether she was deaf and dumb! To woo this girl from the bosom of her merchant family, and to keep her respectability in the eyes of New York’s Puritanical middle class who must be enticed to buy things, William and the Carnes needed the propriety of having a gentlewoman chaperone onboard. This foreign girl was Margaret’s passage into the Great World.

“It is a hard journey though,” William was saying around a mouthful of kippers, brows furrowing with fledgling concern. “And you, so delicate!”

He must not be allowed to think further down this road. So Margaret let her eyes fill with tears for the first time in four or five years, raised them to his (immediately amorous) face, put her hand demurely on his sleeve, and said: “You’re so good to think of me, William. I do get lonely. I really would love the company.”

long story short…

You should approach your organization’s narrative strategy the way you approach any other piece of strategic work. Consider:

What are your narrative goals?

What routines, systems, and processes do you have for executing your narrative strategy?

Way to go April! So glad to hear you’re continuing to work on your fiction. I loved these pages when I first read them and I still do!

So good to see these pages again. Just as rich, compelling, and beautiful as I remember them! ... and re: "blank stupor" LOL--I can relate!