King crab legs and education jargon

What we can learn about narrative clarity from the No. 1 Chinese Dragon Buffet and three “community-centered” education organizations

When I was a kid, the only restaurant my parents took us to was the No 1. Chinese Dragon Buffet. As a rule, they weren’t big believers in eating out, considering it an unnecessary extravagance. But the No. 1 Chinese Dragon Buffet was different. It was bang for our buck. And as long as my parents could pass me off as a 12-year-old to qualify for the discounted kid rate—which they did until I was 15—it was extra bang.

On No. 1 Chinese Dragon Buffet Saturdays, we didn’t eat breakfast so that we would be empty and ready to cash in at the restaurant. We timed our arrival between 1:30 and 2:00, late enough so that, if we lingered, our meal could tide us over for dinner, but early enough so that we still got the lunch rather than dinner rate. My mom supervised the filling of our plates like a general. Her strategy: stock up on the menu items that either sounded the most expensive or contained the most expensive ingredients.

In retrospect, this strategy meant that our plates were a mishmash. Herb butter salmon, beef and broccoli, teriyaki chicken skewers, custard tarts, stuffed clams, red bean buns, prime rib, chunks of tropical fruit, and out-of-season vegetables (we ate in-season at home). All topped off with a huge pile of king crab legs. Gordon Ramsay would have been hard pressed to find a “story on the plate.” It wasn’t surf and turf. It wasn’t appetizers or mains or desserts. It wasn’t flavors that somehow melded in symphony on the palette. It wasn’t even Chinese.

Sometimes, I think of those loaded No. 1 Chinese Dragon buffet plates when I come across a piece of incomprehensible social sector storytelling. Take this speaker intro that a friend recently heard at a Zoom event and obligingly emailed to me: “She will explain how she views this benchmarking data directionally…. yada-yada… ecosystem… yada-yada… bifurcate…yada-yada… stakeholders… yada-yada… transformational… yada yada… actuating.”

I think it’s fair to say that the yada-yadas and ellipses are not what makes this introduction incomprehensible. It’s the sheer density of jargon, words seemingly grabbed as if at a buffet because they sounded the most expensive. We’ve probably all heard an introduction or a panel description or a mission statement that sounds relatively similar.

Jargon is the social sector’s greatest barrier to effective storytelling, because it promises sweeping societal change while remaining vague as to the specifics. It tricks us into feeling like we’ve made a bold and powerful statement when, in actuality, we’ve said nothing concrete. The consequences are real. Not only might our audience be confused about who we are and what we do, but our story may disappear among all the other social sector stories that employ the same jargon. The speaker at the Zoom event my friend attended probably had a distinct and impressive story of how they came to their work. But nobody in the audience got that story because their brains were too busy filtering through the grandiose vagaries of directional benchmark data, bifurcation, and transformational ecosystems.

So what makes jargon… well… jargon?

As I wrote in a previous post, we can separate social sector words into two categories. Staple words leave no room for interpretation or inference. They include everyday words like thumbtacks, corn, and hats, or technical language—like myocardial, ACE filter, and demi plié—that are core to the body of knowledge needed to the work of a profession. Power words connote weightiness and value—like king crab legs—but can change meaning depending on context. They include nouns like equity, community, and joy; verbs like amplify, leverage, and transform; and adjectives like diverse, impactful, and paradigm-shifting.

Generally, people have a sense of what power words can mean. But in the social sector, we’ve developed a bad habit of throwing around so many power words without considering what we mean that they become gobbledygook—not just to others outside our profession, but to everybody. That’s social sector jargon.

The bottom line about jargon is that it’s contextual. It’s a state of being. No word is only jargon (except maybe for borderline-fake words like “actuating”). When chosen with careful consideration, a power word can succinctly add a world of meaning to our organizational story. But when snatched from the linguistic buffet and tossed carelessly into our story, a power word becomes jargon.

In the second issue of every month, for the next few months, I’ll pull a couple lists of top ten jargon from different sources for one social sector, e.g. education, the environment, public health. Then, I’ll choose one of those words and offer three use cases for each: one in which the word is definitely jargon and detracts from the organizational story, one in which the word adds value to the story, and one in which the word lies somewhere in-between.

for example: education

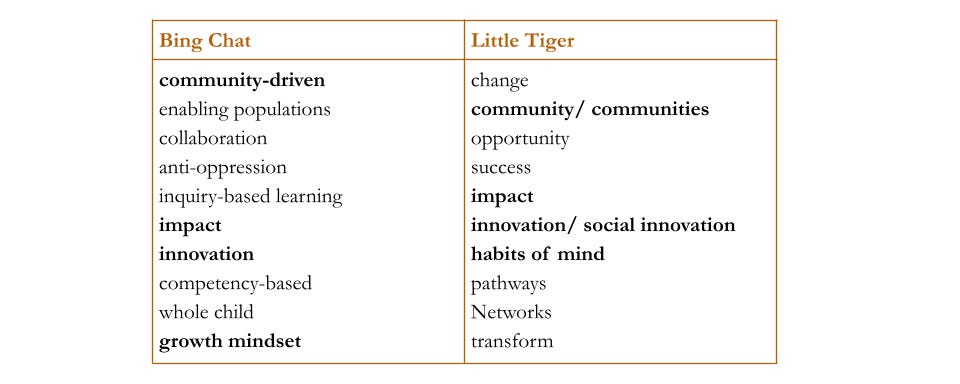

Today’s top ten lists come from the (U.S.) education sector. The first list I offer comes from Bing Chat, which uses the same large language model as Chat GPT, but is more up-to-date since it incorporates web results into its answers. The second list is one I curated myself just for fun, using what I’m sure is a janky methodology, which you can check out in the footnote.1 They are listed in no particular order.

Let’s look at “community.” I wasn’t surprised to see it appear on both lists. Community seems to be one of those must-have words in the education sector today, reflective of a changing social ethos that no longer celebrates outsiders sweeping into failing schools to save the children, but instead advocates for partnerships that respect community input, knowledge, and resources. This sentiment is captured by increasingly popular catchphrases such as “not about us without us.” The initial commendable push to center communities in decision-making has led to an explosion of the word in education sector storytelling, to varying effect.

Straight-up jargon→ an insubstantial (unsubstantiated) and forgettable story

The tagline of Illumina’s Corporate Social Responsibility arm is to “empower our communities.” So, the question is: who are Illumina’s communities? And in what way does Illumina empower them?

First, it seems that Illumina’s communities include anywhere where they have commercial offices. Scale varies from San Diego to all of India. A broad community! Second, it seems that Illumina’s CSR has two major streams of work: 1) grantmaking in the areas of STEM education and genomics, and 2) structures and incentives for their employees to volunteer in their communities. While both streams of work certainly qualify as community investments in education, the link to community empowerment is unidentifiable. It feels as though Lumina decided on a CSR strategy, and then chose the power words “community” and “empower” to describe that strategy without considering whether they really fit. Jargon… with all its consequences! Rather than telling a compelling and distinct story about the good work that Illumina does do through their financial and employee time investments, they instead tell an insubstantial story that fades into the noise of a hundred other mission-driven orgs also telling insubstantial stories about empowering communities.

On the cusp→ a confusing story

Empower Schools believes “that solutions should be locally driven and designed to meet the unique context of each community.” They add “capacity, expertise, and strategy to empower communities to drive local solutions and realize the hopes they have for their kids.”

Like Illumina, Empower’s story is built around the themes of empowerment and community, but its specific focus on school design renders it immediately less jargony. In fact, it sounds pretty good! But eventually the same questions arise. What does Empower mean by locally-driven? Does that mean the community makes all the decisions? That they give input through surveys? That they generate the ideas? And what does Empower mean by each community? Is it each school community of principals, teachers and students? Each geographic community of families and local business owners?

We start to get a glimmer of understanding if dig into their project synopses and publications. For example, Empower says: “Our support is truly customized to the needs and desired outcomes of each of our partners. We collaborated with the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, Springfield Public Schools, and the Springfield Education Association to help design, launch, and initially implement the Springfield Empowerment Zone Partnership…” In turn, the Springfield Empowerment Zone Partnership’s storytelling is flush with testimonials from teachers, principals, and administrators talking about their participation in designing schools.

I infer that by community, Empower means state and city educational institutions of power and education professionals who work at these institutions. It’s a fair definition of community, but it’s a far cry from the meaning I’d originally assumed—students and their families—based on Empower’s story headlines. Confusing! I’ll also note that it took me some rooting around and some inferring in order to nail down this definition—time and effort that the average event attendee, donor, or newsletter recipient probably won’t invest.

Used with intention→ a succinct and distinct story

Northeastern University’s Service Learning program engages students “in hands-on service to address community needs, learning by applying course concepts to their experiences, and reflecting on those experiences back in the classroom.” The program identifies “partnerships with schools, neighborhood agencies, health clinics, and nonprofit organizations” as part of academic coursework.

It’s immediately evident who Northeastern means by the community. Community is the people who live in the geographic locale that Northeastern occupies—Boston—as well as the organizations who serve them. Northeastern isn’t using “community” in the trending sense of pulling in the community to make or inform decisions, but in the old sense of community service. While this definition may be more or less compelling to various audiences, it’s certainly upfront. And succinct! We get the point right away. And it follows through in other pieces of Northeastern’s storytelling.

long story short…

The moral of the story (or of this post) is not that we should avoid using any of the words on these lists. It’s that we should approach language with the consideration and craft of storytellers, rather than with the zeal of buffet-goers looking for fancy fixings.

I should also note that jargon, like language in general, is reflective of its time and ethos. Ten years ago, these lists might have swapped out “community” for “blended learning” and “innovation” for “achievement gap.” Ten years from now, this list will look completely different yet again. There’s also a difference between the language of institutions that have been around for decades (which informed my list), versus the language of newer education organizations that seek to “disrupt” the status quo. If we want to get meta about it, “disrupt” would probably show up as one of the top ten jargon for that subset of organizations.

By its very definition, jargon goes in and out of style. By choosing our words with deliberation, we can avoid telling a story that is one day not only incomprehensible, but also out-of-date.

I’m always curious about the methodology behind creating a top ten list, so thought I’d try my hand at creating my own. Granted I’m not a researcher, so the methodology is janky. But here is what I did. I created a rough database of language by copying and pasting: (1) language from the homepages and/or “about” pages of ten “most influential” US-based organizations in the education sector, as identified for me by ChatGPT. These included: Teach for America, DonorsChoose, Khan Academy, Reading is Fundamental, The Posse Foundation, The College Board, City Year, Boys & Girls Club of America, 826 National, and TeachPlus. (2) ten recent education articles from three prominent social sector publications, including The Stanford Social Innovation Review, the Chronicle of Philanthropy, and the Harvard Business Review, and (3) ten panel descriptions from a prominent education sector conference, in this case the 2023 SXSW Edu. I then searched for and deleted education staple words—words that, based on the aforementioned definition, aren’t open to interpretation and are core to the job—from the database. For example, some of the staple words I deleted include schools, students, teachers, curriculum, and policy.” I then entered the database into WordCounter to do its magic.