My logic model enables mission creep

How can starting with story help rein us in from doing everything for everybody?

In the social sector, we complain a lot about mission creep.

I’ve worked at organizations where everybody was so deeply in the weeds of the work that we couldn’t separate one issue from another. Say our mission is to promote early literacy… but we realize that kids can’t thrive as readers unless they have full tummies and access to books where they can see themselves in the main characters, so we build a nutritious meal program and start printing our own picture books. I’ve also worked at organizations where we’re so desperate for money that we apply for every funding opportunity under the sun, then find ourselves restricted by grants to do work that is only tenuously related to our mission. Say there’s a ton of funder interest in middle school STEM, so we begin churning out grant applications for STEM literacy projects. Suddenly, we find that our early literacy organization has swerved into the business of hunger relief, culturally responsive publishing, and middle school STEM instruction. Mission creep!

As a storyteller, I often come across a parallel phenomena that I call story creep… although it’s never really a matter of story creeping but of story falling apart. How do you tell the story of an organization that focuses on early literacy, provides meals and publishes books, and also dabbles in middle school STEM instruction on the side? In other words, how do you tell a compelling story about an organization that tries to do everything for everybody? You can’t.

While mission creep sounds like a strategic issue and story creep sounds like a communications issue, they boil down to the same problem: confusion where there should be clarity. With that confusion comes an onslaught of other problems. Leaders mix up their priorities. Staff become overworked, do work that’s not in their job descriptions, or do work that doesn’t fit their skill sets. Everybody else—donors, volunteers, partners, community members—get confused about the organization’s identity: what change they seek, what they do, how they do it, and who they are. It’s a mess!

Theoretically, the strategic planning process should help us avoid the pitfalls of creep. But I’ve found that it’s far more effective to assess mission alignment through the lens of story.

Logic models actually enable creep

When social sector organizations make decisions about what they do, they tend to structure their thought process using at least one of three things in the social sector strategy toolbox:

the intended impact statement popularized by Bridgespan;

the theory of change popularized by the Aspen Institute;

and most commonly, the logic model, popularized by the Kellogg Foundation.

(We’ll table the bizarre fact that these three institutions have basically directed the way the entire social sector in this country thinks about strategy. But that’s a conversation I’d love to have another time!)

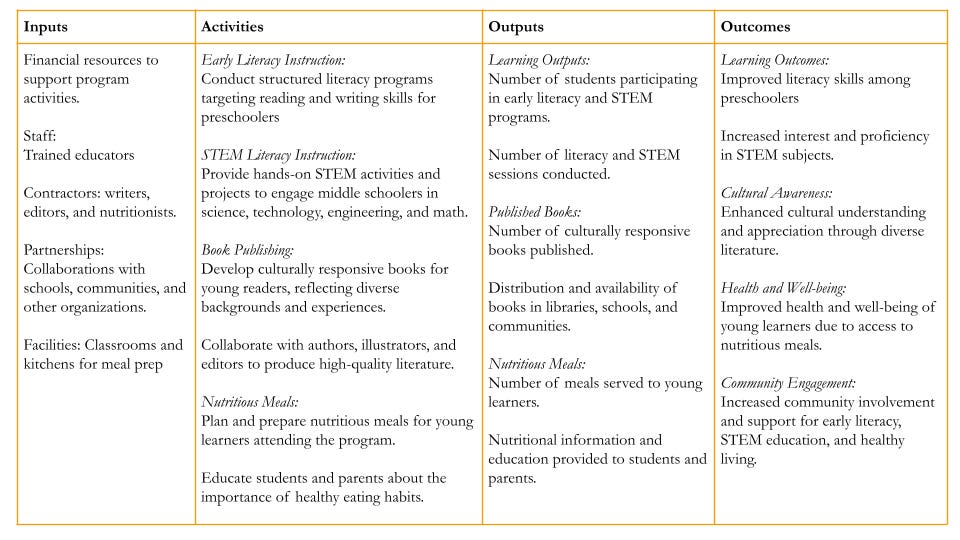

These tools are really great for categorizing, making sense of, and measuring what we’ve already decided to do—which is great for the last era of grant writing—but they’re terrible for assessing what to do and what to cut. In fact, these tools often don’t help organizations plan at all, but instead help them justify. We can pretty much justify anything in a logic model! Proof: here’s what a snapshot of that fictitious early literacy organization’s logic model, as generated by ChatGPT, might look like.1

By neatly categorizing everything in columns, and making connections across the columns, the logic model manages to make it feel as though everything this organization is doing is cohesive and purposeful and strategic… when, in fact, it’s not.

Stories require us to be compelling… and make sense

In contrast, I bet anyone looking at the early literacy nonprofit’s website and social content will see a mess of mixed messages—who they say they are on their homepage probably doesn’t line up with what they say they do on their programs page…which probably doesn’t line up with what they show they do via Instagram…which probably doesn’t line up with the research they share they care about via LinkedIn! I’ll also bet that if you ask any employee to summarize what the organization does in a sixty-second elevator pitch, they’ll either be at a loss or start babbling incoherently. In fact, this is what Gemini (Google’s AI application, recently infamous because of its built-in instructions to generate images of “diverse” people) came up with, when given this task:

Imagine a future where all children have the chance to thrive. That's what drives our program. We target the crucial early years, offering preschoolers structured literacy instruction to build a love of reading. For middle schoolers, we make science, technology, engineering, and math come alive with hands-on projects. To foster cultural understanding, we publish diverse books that reflect the world our children live in. And, because you can't learn on an empty stomach, we provide nutritious meals and education. Our results speak for themselves: improved literacy, STEM skills, cultural awareness, and healthier kids. Join us in empowering young minds and building a brighter tomorrow!

When I later asked Gemini to evaluate this story for strategic clarity and consistency, these were the headlines of its response:

“The story lacks focus and suffers from a diluted message.”

“The wide spectrum of programs (literacy, STEM, cultural awareness, nutrition) makes the organization’s central area of expertise unclear.”

“It’s difficult to pinpoint what specifically sets this organization apart.”

In other words, the story is a mess—because it’s not actually a cohesive story at all, but instead a disjointed collection of ideas and activities.

Story offers an intuitive and uncomplicated lens through which to both plan and examine our strategy. Stories in the western tradition have followed the same basic formula for centuries, which can be mapped onto organizational narratives: one clearly defined inciting conflict (the problem that triggers the need for your work), setting (where the work takes place), journey (what you do to solve the problem), character (your org values and approach), and resolution (your intended impact).

When we examine the early literacy nonprofit’s strategy through this narrative litmus test, it’s immediately and glaringly clear that we’re telling a confusing story with way too many plotlines—and that we have some hard decisions to make in order to get our story back on track.

Ultimately, rather than justifying every strategic and non-strategic decision we’ve already made, story forces us to be accountable for those decisions and to change course if needed. A bonus: when we use story to refine our strategy, we refine our communication as well!

My prompt: “Create a logic model for an early literacy organization that provides early literacy instruction and STEM literacy for middle schoolers, publishes culturally responsive books for young readers, and also provides nutritious meals for young learners.”